In the archives of the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin, our writer found a previously unknown audiotape of an interview with a woman who’d been born into slavery.

One day in the early 1940s on the south side of Austin, Texas, a young white man named John Henry Faulk carried a very large recording machine into the home of an elderly black woman named Harriet Smith. The two were neighbors: Faulk’s family lived only four blocks from Smith, and she had known him since he was a baby. He was in his late twenties when he brought the recorder to her house, and she was in her early eighties. Faulk addressed her as “Aunt Harriet.” She called him “Mr. Faulk.”

Many years later, Faulk would remember Aunt Harriet as an amusing old woman about whom people liked to tell funny stories.

Faulk knew all about telling funny stories, especially about blacks. He had been doing this since high school, reciting Shakespeare plays, for instance, as though Hamlet and Henry IV were characters on Amos ‘n’ Andy. He cheerfully called one such performance a “nice little nigger story.”

As a student at the University of Texas at Austin, he performed these stories at social gatherings, including parties organized by his professors. He studied with famed Texas folklorist J. Frank Dobie, as well as John Lomax and his son Alan—who had “discovered” blues musician Lead Belly in prison in Louisiana and would later find and record Muddy Waters in the Mississippi Delta. When Dobie and the Lomaxes first met Faulk, they were impressed by his uncanny ability to ape the speech of black Americans—often as a joke.

And yet, by the standards of the day, Faulk was far less racist than most white Southerners. A few years after he interviewed Smith, he would join the NAACP. His upbringing had been unusual: His father was a longtime socialist who advocated for racial equality, and the family had lived in an integrated neighborhood in Austin. Faulk grew up playing with black children. By the time he visited Harriet Smith’s house, he had been tapped for an antiracism project—audio recording black church sermons in heavily African-American parts of the Brazos River Bottom region of East Texas. The Julius Rosenwald Foundation, an early 20th-century fund renowned for promoting black education and culture in the Jim Crow South, bankrolled the work.

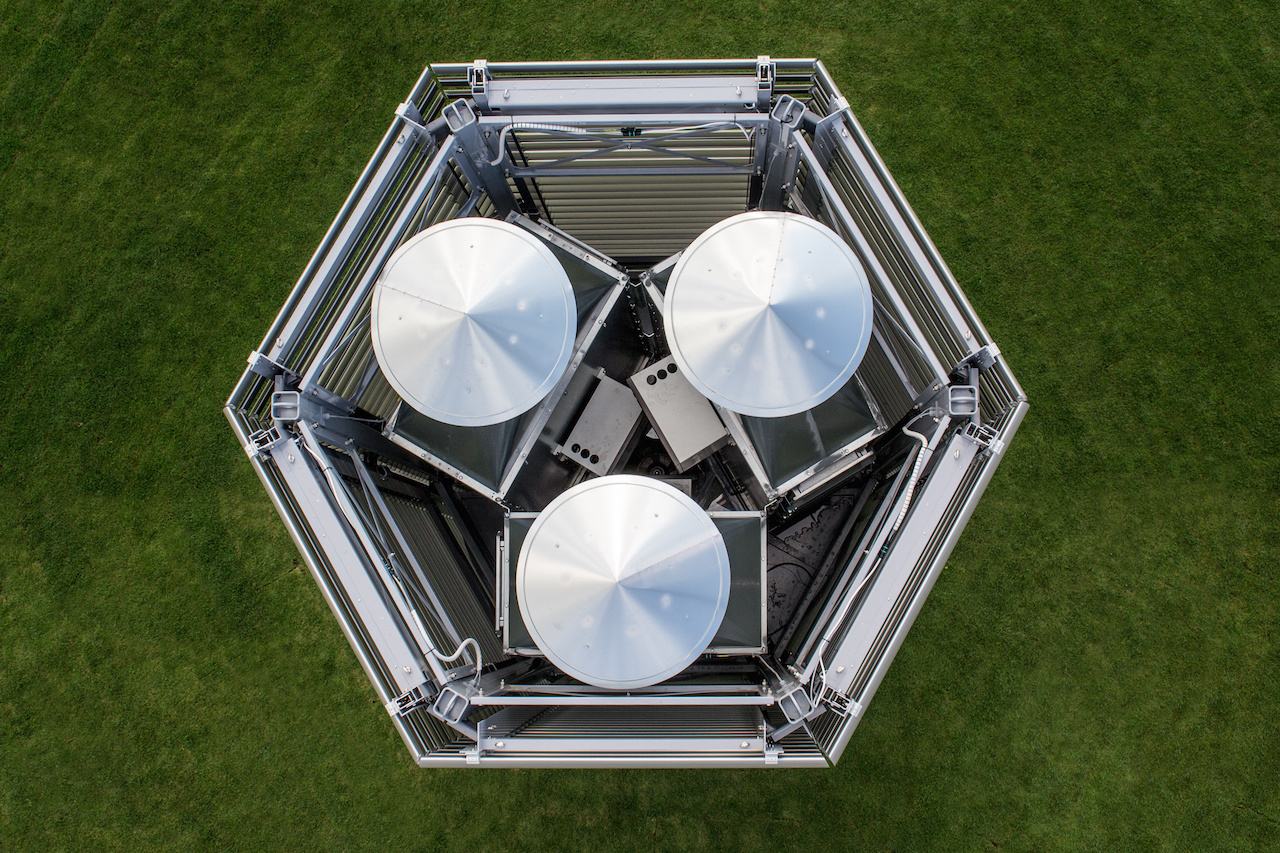

To carry out the project, Faulk was given a machine that weighed more than 130 pounds and etched grooves onto a metal disc while the speaker talked into a microphone. He stored this cumbersome equipment in the back of a car and drove it to rural Texas in late 1941. There, he recorded black congregations singing and shouting, their preachers sermonizing, and families weeping at funerals. He also took the gear to Negro house parties in his own neighborhood in Austin, where he recorded young men singing blues and young women crooning Billie Holiday.

As I discovered recently, he also went to Aunt Harriet’s.

***

One of the WPA’s projects was to record the reminiscences of elderly blacks who had been liberated from bondage at the end of the Civil War.

It wasn’t Smith’s only encounter with a recording device. She was of continuing interest to Faulk because she had been a slave in the 19th century, and in the previous decade, Faulk’s mentors, John and Alan Lomax, during trips they made through the South to collect folk music, had recorded some interviews with former slaves. By 1937, John Lomax was the national folklore advisor for the government’s Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), which was part of the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration (the WPA). One of the FWP’s projects was to record the reminiscences of elderly blacks who had been liberated from bondage at the end of the Civil War. FWP workers interviewed about 2,300 people. After the FWP was over, the Library of Congress continued to collect interviews, and Faulk participated in that effort. Almost none were audio recorded—the vast majority of the interviews were simply written down by the government workers as notes then transcribed onto paper and eventually filed in Washington. Today, these written first-person accounts of life under the peculiar institution can be downloaded for free from Project Gutenberg. The Library of Congress also posts them.

***

A few months ago, another white man, Dylann Storm Roof, visited a black church—this one in Charleston, South Carolina—and shot to death nine congregants. Months before committing the murders, he posted a comment on a white supremacy website that he administered, noting that one thing leading him to consider black people as racially inferior was his study of ex-slave narratives. These narratives showed, Roof wrote, that antebellum American slaves were happy in their bondage. Their happiness, he wrote, was being kept secret. This infuriated him.

I have reviewed many of these narratives. I started months ago, after discovering that one set of my great-great-grandparents owned two female slaves (and that another great-great-grandfather fought in the Confederate Army). The skeletons of this history had for generations been closeted in my liberal, civil-rights-activist Texas Jewish family. This is a family who went to interracial fellowship gatherings in segregated Houston during the 1950s and encouraged its white children (including me) to ride at the back of the bus and to use restrooms and water fountains marked “colored” instead of “white.” Using an easy-to-find document on ancestry.com, the 1860 Federal Slave Census, I discovered my family’s slavery secret. I called a reunion of the kin to break the news. Then I developed an almost obsessive interest in the ex-slave narratives.

Many interviewees told cheerful stories about their enslavement.

Going through my first few scores of them, I was shocked to notice the same thing that Roof mentioned—that many interviewees told cheerful stories about their enslavement.

Jim Allen, for instance, was an 87-year-old former slave in West Point, Mississippi when the WPA interviewed him in 1937. He talked about how much he loved his owners: “Ole Miss was so good, I’d do anything fer her.….”

John Cameron, from Jackson, Mississippi, expressed similar feelings: “My old Marster was de bes’ man in de worl’.… Us had plenty t’ eat and warm clo’es an’ shoes…us ain’t never min’ workin’ for old Marster…that meant good livin’ an’ bein’ took care of right.”

Anna Baker, at 80 years old, in Aberdeen, Mississippi, recalled running to greet her owner when he returned to the plantation from town: “Here come de marster, root toot toot!” Josephine Bristow remembered her master returning from journeys and delighting her with remarks such as, “Yonder my little niggers! How my little niggers?”

And Harriet Smith, the funny old woman in Austin, told John Henry Faulk that her white owners were “good to us. Good. They never whipped none of their colored people.”

***

Confused about these apparent encomiums to slavery by people who themselves had been slaves, I put down the narratives and sought out critical analysis by historians and other scholars. There are, it turns out, many reasons why elderly black people in the early 20th century might have reflected happily upon their bondage in the 19th.

One reason, the literature points out, is that almost all of the WPA interviewers were white Southerners. Some had grandparents (and even parents) who had owned the very people they were interviewing—in Southern towns still under the terroristic grip of Jim Crow. (Faulk’s grandparents had owned slaves, though he never talked publicly about that, and it’s likely that his parents had known the family who owned Harriet Smith.) Some interviewers – including Faulk, when he interviewed Harriet Smith — posed leading questions encouraging ex-slaves to emphasize the positive. Faulk asked Smith, “Some folks awful good to their slaves, weren’t they?” Lately it has come to light that when the answers weren’t positive, many WPA regional administrators abridged the transcripts. Or they mothballed the interviews entirely and never sent them to Washington.

Furthermore, many of the interviewees lived in decrepit shacks, wore ragged clothes, and were sick and hungry. The Depression was raging, and Southern blacks, routinely denied government aid because of their race, were especially desperate. Many thought the WPA interviewers, being from the government, could get them food and monetary “relief.” The interview transcripts record them begging for help. Many likely said what they thought the interviewer wanted to hear in order to receive assistance.

Slave children typically experienced something vaguely resembling free, early white childhood, which, over eight decades later, many remembered in a haze of fondness.

But perhaps the strongest and most poignant explanation for fond memories of slavery is that the majority of the interviewees, born in the 1850s and 1860s, were young children during the Civil War. (Harriet Smith was about six and a half years old when Yankee troops finally occupied Texas and declared emancipation in June 1865.) Years later, those children, now elderly, recalled that, even on the most brutal plantations of that period, slaves were not put to hard field labor until they reached the age of 10 or 12. Among enlightened owners, animal-husbandry theories abounded regarding how best to extract maximum, long-term productivity from slaves. One tenet was that the child slave’s body should be well nourished and left at rest until adolescence, to assure good development and hardiness. Thus, except for relatively light jobs such as caring for younger children, many young slave boys and girls were allowed to spend at least some of their days playing—even with their owners’ sons and daughters. Slave children typically experienced something vaguely resembling free, early white childhood, which, over eight decades later, many remembered in a haze of fondness. This is the “happiness” that Dylann Storm Roof read about. As did I.

***

However, just as I did, Roof undoubtedly also read chilling accounts of the way these children were treated like small animals, even in relatively good circumstances. Henry Brown, from South Carolina, remembered how his owner, a Dr. Rose, “gave me to his son, Dr. Arthur Barnwell Rose, for a Christmas present.” Solbert Butler, also of South Carolina, remembered how his “massa take me as a little boy as a pet,” with a little bed to sleep on at night near the master’s big bed—as a dog today sleeps in its owner’s room on a monogrammed dog pallet mail-ordered from Lands’ End. Jim Allen was also kept as a “pet” – after his previous master lost him in a whiskey debt. Allen recalled that his new master, the creditor, “tuk me, out’n the yard where I was playing marbles. De law ‘lowed de fust thing de man saw, he could take.”

Then, there were far worse circumstances. The mother of J. W. Terrill, of Madisonville, Texas, served, once a week for years, as her white male owner’s concubine. As a result, Terrill was mulatto, the son of “my mammy’s master.” Furious about the existence of his mixed-race issue, Terrill’s father “willed I must wear a bell till I was 21 years old, strapped ‘round my shoulders with the bell ‘bout three feet from my head in steel frame.” Terrill commented to the WPA interviewer that he “never knowed what it was to lay down in bed and get a good night’s sleep till I was ‘bout 17 year old, when my father died and my missy took the bell offen me.”

Then there were the auctions, during which, even if children were not the goods for sale, they witnessed other people on the block and never forgot it. Jake Terriell, during his childhood as a slave in South Carolina, told his interviewer that he “seed slaves sold and you has heared cattle bawl when de calves took from de mammy and dat de way de slaves bawls.”

Children saw and overheard casual murder, with utter lack of response from authorities except to dispose of the bodies. Lou Williams, from Maryland, recalled living “close to de meanest owner in de country…he keeps overseers to beat de niggers and he has de big leather bullwhip with lead in de end, and he beats some slaves to death. We heared dem holler and holler till dey couldn’t holler no mo! Den dey jes’ sorta grunt every lick till dey die…de whole top of de ground jes’ looks like a river of blood…sometime de law come out and make him bury dem.”

“Lawd, Lawd,” Williams concluded. “Dem was awful times.”

***

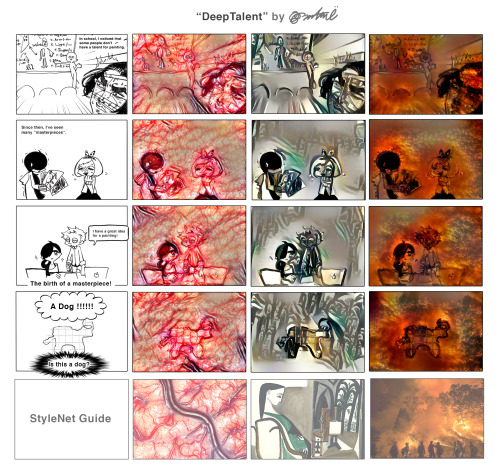

But to the eyes of white transcribers and even contemporary readers, those times probably don’t seem as bad as they would if they had been written down for posterity in Standard English—all those “de’s” for “the,” “jes” for “just,” that man who remembered how he “seed” slaves being auctioned rather than saw them, the children who “heared” instead of heard dying people holler until they “hollered no mo.” All those apostrophes and missing consonants at the ends of syllables, the mangled verbs, and verbs about things that happened past tense yet were uttered using the present. Verbs describing people who, the interviewees knew, had died as slaves many years ago, yet the ex-slaves said of these people that “they die,” as if their deaths were just happening or had not yet happened.

How curious nowadays to read these quirks of English. They were quirks that white writers used to mock black people, even before Mark Twain practically institutionalized the practice. In the pages of Huckleberry Finn, Twain’s black character, Jim, spoke in a riot of misspelling. Twain’s use of “nex’ day” for “next day,” “git” for “get,” “didn’” for “didn’t,” and “uv” for “of” is what linguists call eye writing, because it brings dialect to the eye. To the reader, this orthography makes the speech of people like Jim look different from educated white people’s speech. But eye writing is a cheap, hierarchical trick. In fact, many Americans of different classes, geographic regions, and ethnicities say “uv”, “nex’ day,” and “didn’.”

Eye writing probably targeted blacks more than any other group.

Yet in fiction, funny-page cartoons, and folklore scholarship from the late 19th century until well into the 20th, eye writing was a common way of marking and (consciously or unconsciously) belittling classes of people considered less successful or less than American. Immigrants were one target. Another was white Appalachians (whose speech was extravagantly eye-written in the comic strip Li’l Abner).

Eye writing probably targeted blacks more than any other group. Respectable writers did the work, and respectable readers chuckled. In 1932, the dean of the Texas State College for Women published Chocolate Drops from the South, a collection of what his grandson Edmund V. White III, the renowned contemporary writer about gay life, would many years later deride as “’nigger’ joke books.” The jokes were replete with stereotypes about blacks: that the females were promiscuous and ever ready to cheat on their husbands, that males were happily prone to commit deadly violence with guns, knives, and dangerous household goods. A typical joke in Chocolate Drops has a woman asking “Rufus,” her partner, “Whut is yo’ gwine do wid dat razor?” Rufus answers, “See dem two shoes undah de baid. If de ain’t no man in ‘em, Ah is gwine tuh shave.” Also included is a joke about a lynching. In one of her “My Day” newspaper columns from 1937, Eleanor Roosevelt enthusiastically recommended Chocolate Drops to “anyone who wants a laugh a day.”

Meanwhile, those WPA interviews, which Dylann Storm Roof and the rest of us would encounter decades later, are replete with stories of “happiness” rendered in the most egregious eye writing: “Ever since I a child I is liked white folks…I got a heap mo’ in slavery dan I does now; was sorry when Freedom got here.”

***

There is one tiny set of ex-slave interviews that is unequivocally dignified. These are audio recordings of about a dozen people, made mostly in the 1930s and ’40s. They total some 260 minutes, just over four hours. Some are so clear that you can’t believe they are more than a half-century old; others are scratchy and muffled. Regardless of quality, however, the sounds on these recordings go straight to the ear, unmarred by eye writing. They are unadulterated voices of human beings, reminiscing about their enslavement.

One is a man who (it has since been established) was a great-great-grandson of Betty Hemings, the slave matriarch at Monticello, one of whose children was Sally Hemings, the enslaved mother of six of Thomas Jefferson’s children. A photo taken in 1949, the year he was interviewed (not as part of the WPA, but by a Library of Congress engineer who was also his nephew) shows the man gray-bearded and tall yet bent with age. From his first utterance, he booms, belts, and declaims, like an oracle from an ancient world. “My name is Fountain Hughes!” he shouts. He tells us he is 101 years old, from Virginia, and that his grandfather belonged to the president.

And then, in the absence of eye writing to bemuse, confuse, or amuse us, Fountain Hughes’s voice—the voice of an American who was enslaved—raises our skin with gooseflesh.

So does Harriet Smith’s voice on a recording John Henry Faulk made of her in Austin, which he sent to Washington. Speaking to him in the 1940s, she now speaks to us from the living dead of history—and from the Library of Congress.

***

Click to view slideshow.

Smith’s and the other ex-slaves’ stories were, for a long time, unavailable to the public. Finally, in 1972, the written interviews, filed with the Library of Congress in the 1940s, were published as a mammoth series titled The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography. But the small collection of audio recordings, etched in lacquer and aluminum, remained in storage and mostly forgotten.

Publication of the written interviews corresponded with a rash of interest by sociolinguists in what has come to be known as AAVE, or African American Vernacular English.

Education researchers and schoolteachers had assumed that black students were speech deprived and intellectually inferior. Labov’s investigations showed that, on the contrary, nationwide, African-American vernacular speech was as complex and grammatical as any other dialect.

One of these scholars was Columbia University’s William Labov (now at the University of Pennsylvania), who, in the 1960s, researched inner-city black children’s dialect in African-American communities like Harlem. Education researchers and schoolteachers had assumed that black students were speech deprived and intellectually inferior. Labov’s investigations showed that, on the contrary, nationwide, African-American vernacular speech was as complex and grammatical as any other dialect.

Labov’s work fit well into the era of the Civil Rights, Black Power, and the War on Poverty. It was buttressed when linguists such as J. L. Dillard proposed that the dialect of American blacks came not from fractured versions of white Southerners’ speech, but from an antique, transatlantic pidgin used by European and English slave traders to communicate with one another and with their human cargo. By definition, a pidgin is a language with reduced vocabulary and simplified grammar that is native to none of its speakers. The transatlantic version probably had no verbs inflected for past tense, only one or two pronouns, and a mélange of words from Romance, English, and African languages. By definition, if a pidgin is spoken long enough, children are born who end up speaking it as a native language. At that point it ceases being a pidgin and starts to “creolize,” meaning that its grammar gains complexity, and its vocabulary expands. Dillard believed that, beginning in colonial America, slave children on plantations came to speak a creole similar to those spoken on slave-plantation islands of the Caribbean. And eventually, the creole evolved into a modern dialect: African American Vernacular English.

Take “pickaninny,” a Southern word for a black child. Dillard argued that this word came from pequeño or pequeñiño, Spanish and Portuguese, respectively, for “small.”

Dillard presented intriguing evidence for his thesis. Take “pickaninny,” a Southern word for a black child. Dillard argued that this word came from pequeño or pequeñiño, Spanish and Portuguese, respectively, for “small.” Words from these languages were widespread in the transatlantic pidgin, Dillard pointed out, and some must have been handed down to American Black English.

There was other evidence of creolization. Black vernacular speech tends to omit the “copula,” forms of “be,” as in “He going” and “My father tall.” Meanwhile, the dialect adds “aspect” markers before verbs, such as “done” for the perfective, completed past (“She done put on a clown costume yesterday”) and “be” for the imperfect or habitual (“She always be a clown on Halloween”).

Other linguists disagreed with Dillard that Black English in America derived from pidgin and creole. They thought it was more of a remnant of 18th- and 19th-century white speech, including archaic features—such as “brung” for “brought” and “ax” for “ask”—that almost no white people in America use today but that were common centuries ago in white America and parts of Great Britain.

Finding the tapes was like unearthing a time capsule, and the linguists couldn’t wait to compare ex-slaves’ speech with that of contemporary blacks.

In the late 1980s, the Library of Congress dubbed the ex-slave audio recordings onto tape. Sociolinguists studying black vernacular English got excited—they assumed that even though people like Harriet Smith and Fountain Hughes were interviewed in the 20th century, their grammar and pronunciation were essentially the same as when they were children in the 1830s, ’40s, and ’50s. Finding the tapes was like unearthing a time capsule, and the linguists couldn’t wait to compare ex-slaves’ speech with that of contemporary blacks. The differences would cast light on the evolution of a dialect and show whether it was “converging” with contemporary white speech, as the linguists put it, or diverging because of persistent racial segregation and inequality.

So researchers started listening to the tapes. But they soon realized that people like Harriet Smith challenged sociolinguistic assumptions.

***

For one thing, the ex-slaves did not speak with the comico-linguistic neatness of an Amos ‘n’ Andy show. For every occasion when an elderly interviewee left out the copula in one phrase, in another utterance, a form of “to be” appeared. Fountain Hughes provides a typical example. “We afraid to go,” he said, recalling a night, in his boyhood, soon after liberation, when he was homeless and worried about finding a safe place to sleep. In a previous sentence, however, Hughes had said, “we was afraid to go.” Harriet Smith spoke similarly. She almost always said “was” and “were” when referring to the past. But then she didn’t, as when talking about her younger siblings, born in freedom, versus an antebellum cohort of children that included her: “We the only two in slavery times.”

In trying to interpret grammatical variations in ex-slave speech, another challenge researchers faced was that they knew very little about their audiotaped informants. They knew that most had been children in bondage. But what happened after the Civil War? Where did they live? How did they make a living? Did they receive any schooling? What exposure did they have to white speech, first as slaves and then as free people?

Information like this is crucial to understanding how and why a person speaks as she does. It wasn’t just that the WPA interviewers hadn’t asked— sometimes they had. A bigger problem was that years after the interviews yet still before the Internet, it was exceedingly difficult to research the biographies of humble people who were no longer alive.

And perhaps the biggest problem: Even when an ex-slave provided detailed information about life during and after liberation, the data sometimes got misfiled, or worse, ignored.

Take Harriet Smith. When Smith correctly told Faulk she was from near the little, Hill Country Texas town Buda, he at first repeated the town name correctly, then changed the “d” sound to “l.” This second pronunciation was wrong, but Faulk’s voice prevailed over Smith’s. The Library of Congress interview transcript has her as being from near “Beullah”—a non-existent name in the Texas geography lexicon (a town named “Beulah” with one “l” did briefly exist at the turn of last century, but it has no relationship to Buda or to Harriet Smith).

***

Just as anyone can sit in a bathrobe today and play with Ancestry.com to find out which white people owned slaves, it’s also easy to learn where the slaves lived after they were freed. Starting in 1870, the census shows Smith as a young teenager in a rural community just about twenty miles south of Austin, in Hays County, Texas. She stays in Hays County until the census finds her in 1920, at age 62, in Austin, only doors from Faulk’s house. There is no evidence that Smith ever lived elsewhere, and when she talks about her life on the recordings, she talks only about these places—in detail.

It seems that neither Faulk nor those who later analyzed Smith’s utterances really listened.

But it seems that neither Faulk nor those who later analyzed Smith’s utterances really listened. For years the Library of Congress, and every book and scholarly article that has mentioned her, have described her as an ex-field-slave from Hempstead, Texas.

Hempstead is notorious lately. It is where Sandra Bland, a 28-year-old black woman, died in a county jail this year, after being stopped and arrested by a state trooper who violated her rights. Hempstead is more than 100 miles from Hays County and Austin, in a region of East Texas with a terrible history. Before the Civil War and long into Jim Crow, the economy of Hempstead and its environs derived from cotton and plantations; its culture was plagued by racism that was entrenched and violent. Between 1877 and 1950, Waller County, which encompasses Hempstead, had far more lynchings than most other Texas counties.

Faulk knew how bad things were there. Driving through the area in 1941 with his recording gear, he talked to a black woman who remembered another woman, a mother, who “refused to allow her little 7 yr. old boy to go work for some white man,” as Faulk wrote to Alan Lomax. “She sassed the white man and he came back and killed her.” Faulk quoted another black woman complaining that in Hempstead proper, “they won’t let us Negroes have chu’ch aftuh 10 at night.” A man remarked that, though the Civil War had been over for generations, “The folks down dere ain nevuh heahed dey’s free yit.”

“Chu’ch.” “Nevuh.” “Yit.” Albeit with a pen instead of his voice, Faulk couldn’t help doing Amos ‘n’ Andy.

For sociolinguists studying the history of Black English, it’s vital to know about things like plantations and lynchings. Pidgins and creoles are thought to have developed when slaves had little contact with whites, especially in brutal plantation economies, where relatively few owners lived among overwhelming numbers of blacks. That was the situation in Hempstead. But not in Texas Hill Country, where Smith grew up and where the economy was dominated by livestock breeding on small spreads with a handful of slaves apiece, and where white families lived in relative intimacy with their chattel. Smith’s mother borrowed her mistress’s gray horse to run errands.

Smith told Faulk all about this. She told him the names of her owner and his brothers, a prominent family—one brother was John Wheeler Bunton, a signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence. No doubt Faulk and his family knew the Buntons. The census shows that before and after the Civil War, they lived exactly where Smith said they did, in Hays County, just south of Austin. But when Faulk sent Smith’s interview to Washington, it must have been bundled with his church-service discs. An apparent clerical error turned Smith into a field laborer on a big East Texas plantation—even though she described herself in the audio as a “nurse,” meaning a babysitter during slavery, whose grandmother had been a midwife (apparently for white as well as black women), and whose mother was the white Bunton family’s cook. All this means that Smith’s linguistic world was probably quite different from what sociolinguists have supposed—far more integrated with that of white people.

And they were not just any white people. Another fact about Harriet Smith emerges easily nowadays via one of those bath-robed perusals of Ancestry.com. In her interview long available from the Library of Congress, Smith tells Faulk that her owner during slavery was “Jim Bunton, the baby boy.” She was talking about James Monroe Bunton, the youngest of several slave-holding brothers out on the ranches and farmlands near Austin. One, Robert Holmes Bunton, had a daughter named Eliza. Born in 1849, she was destined before the Civil War to be a slave holder by inheritance–perhaps even to receive one as a Christmas gift or wedding present. During visits to her extended family, she may have played with an item of her uncle’s property: the young child Harriet Smith. Eliza was the grandmother of President Lyndon Baines Johnson.

***

This year, not long after I learned about the slaves in my family, I had a chance to go through John Henry Faulk’s archives at UT Austin’s Briscoe Center. Faulk left behind hundreds of tapes that are now MP3 files. I listened, aghast, to his “nigger stories.” I sampled his spoofs of conservative yahoos and heard his lovingly recorded East Texas black church services from before World War II.

Then I noticed an MP3 marked “Harriet Smith.” I recognized the name from that obsessed time when I’d plowed through the ex-slave narratives. I listened and realized I was hearing 17 minutes of a recording that Faulk had somehow neglected to send to the Library of Congress. I called an archivist there. He said they had many other minutes of Smith, of course—the stuff filed for years under “Hempstead, Texas.” But the archivists at the Library of Congress didn’t have this segment. They’d never heard of it.

The tape I discovered is in some ways no different from the Harriet Smith material that scholars have known about for decades. People used to use the bark from live oak trees to make medicine, she reminisces in response to Faulk’s questions about her youth. Her grandmother baked “fine” cakes for Sunday dinner. Panthers once roamed the area and killed the family’s calves.

She describes children being rounded up to be sold at auction. It wasn’t a white person who did the rounding up. It was a “colored man,” Smith says, perhaps to maintain calm among the children, to keep them from suspecting they were about to be sold.

But in this same interview, Smith gives utterly chilling reminiscences of slavery that I have not seen or heard in other narratives. She describes children being rounded up to be sold at auction. It wasn’t a white person who did the rounding up. It was a “colored man,” Smith says, perhaps to maintain calm among the children, to keep them from suspecting they were about to be sold. The colored man, Smith tells Faulk, “carry these children down.…He say, ‘Bid that child a thousand dollars’….Sold ‘em just like you sell your stock in Austin.”

And the most nauseating recollection of all: Smith remembering a conversation with a preacher she knew, who told her about a woman whose young son was sold from her. The son grew up, and after freedom, Smith says, he apparently met his mother and the two didn’t know they were kin. “He married her own son and didn’t know it,” Smith says.

“Lord, have mercy!” Faulk says, shocked. Apparently he had not noticed what you might have just now: that Smith used the masculine pronoun “he” to represent a mother. Pronoun reduction—changing “she’s” to “he’s”—is a classic feature of a creole. Maybe it provides evidence for the linguists’ “creolization” hypothesis; maybe it doesn’t. One thing is certain: If one were too attentive to the fine points of Black English grammar, one might forget that Smith was describing something beyond grammar—that two black people were forced into one of our culture’s worst nightmares. Parent-child incest.

***

Smith’s own family seems to have clawed itself out of the horror of slavery and made heroic lives for themselves. Here again, Faulk paid no attention.

In the recorded interviews, Smith drops myriad crumbs of information about her childhood in Hays County, near the little town of Buda. In the 1870s, a white man sold a few hundred acres of adjacent land to a group of freed slaves, including Smith’s parents, Clarisa and Elias Bunton. They called their new, all-black agricultural colony Antioch, after the ancient Greek city known as the cradle of Christianity. Smith’s family not only farmed their land in Antioch, but in 1874 they also donated a parcel to build a school for the colony’s black children released from bondage.

*********************

John Henry Faulk died in 1990; his grave is in Austin. Within a generation of his recorded encounter with Harriet Smith, Faulk had largely abandoned his imitations of black dialect. In 1974, on National Public Radio, he told a folksy story about Christmas in rural Texas in which the black and white characters all talked exactly alike. A few years later, he confessed to an interviewer on Austin television that he felt “uncomfortable” with the eye writing of his youth.

Harriet Smith died in 1946, 69 years before Dylann Storm Roof got so upset about the ex-slave narratives, and an equal number of years before Sandra Bland was arrested and died in jail in Hempstead.

Smith is buried in an all-black cemetery in the old black agricultural colony Antioch, nowhere near Hempstead. Sandra Bland lies underground in the suburbs of Chicago.

In South Carolina, Dylann Storm Roof awaits trail for multiple murders and faces a sentence of death.

The post Hearing Aunt Harriet appeared first on JSTOR Daily.